Intersectional subgroup fairness is not intersectionality

machine learning intersectionality by Vagrant GautamThe highlights from Ovalle et al. 2023, our latest paper critically reviewing and reimagining the use of intersectionality in AI fairness.

In the last decade, intersectionality has become something of a buzzword in diversity and equity circles, and is commonly misinterpreted as being exclusively about how people at the intersections of multiple minoritized identity categories experience "more" oppression.

Intersectionality is in fact a much more complex and nuanced framework for examining society. It posits that systems of power and oppression interlock to produce social inequality, and that this produces qualitatively different outcomes for different groups of people. In Lisa Bowleg's words, Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman. From its very conception, intersectionality has had the explicit goal of obtaining political and social justice - through intellectual activism, yes, but also through legal advocacy, movements for prison abolition, participatory action, etc. Its activist roots make it a framework that requires both critical inquiry and praxis (i.e., practical action, not just academic theorizing) to examine and dismantle systems of power at all the levels where they exist - socially, structurally, politically.

Intersectionality thus has great potential for application to any field that studies societal inequalities and seeks to eradicate them. AI fairness is one such example, with a growing body of papers using intersectionality in their titles or motivation. We surveyed a number of these papers in our work, seeking to answer the following questions:

- How is intersectionality discussed in the AI fairness literature?

- What are the gaps in how it is used in AI fairness, as opposed to in core intersectionality literature?

- Can we translate these gaps into recommendations for us to do better AI fairness work going forward?

What "counts" as intersectionality?

The broad scope of intersectionality is sometimes considered one of the reasons it's been so successful as a travelling theory. A more practical consequence of its breadth is that everyone isn't always agreeing with each other; we've now read original texts, critiques and counter-critiques of intersectionality, spanning critical theory, Black feminism, legal studies, cultural studies, political science, sociology, and many more fields.

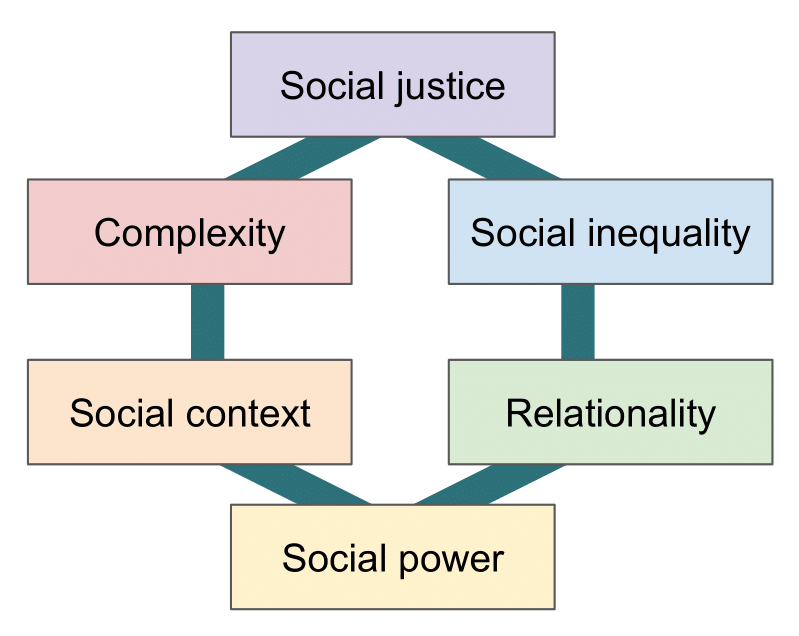

In the end we settled on grounding our study with Collins and Bilge (2020), a book that synthesizes decades of intersectionality literature and comes up with six key tenets of intersectionality. For each tenet, we came up with 3-4 questions to guide our paper reading and see what patterns came up.

What did we learn?

Our annotations gave us quantitative data for an inductive analysis and our guided paper-reading and weekly discussions gave us rich qualitative observations for a complementary deductive analysis. We squeezed a lot of juicy findings into our 10-page paper so read that for more, but I will highlight my top 3 below:

-

Overwhelmingly, AI fairness researchers reduce intersectionality to intersectional subgroup fairness, i.e., showing that an algorithm is fair (for some definition of fair) to Black women to the same degree as it is fair to Black men and to white women. Quantitatively, this finding translates to a high level of engagement with the "complexity" tenet of intersectionality.

-

Power, relationality and social context were the tenets with the lowest engagement, and these results are related. Papers often neglect to situate their work within a specific social context (country, language, group of users) without which it is difficult to engage in relational thinking - to see the relations between different groups in a society, the decisions we make as researchers, the technical artifacts we produce, etc. Relational thinking means acknowledging our power as AI system builders, something most papers didn't do.

-

Citational praxis is questionable at best. Some papers define the term but cite no core intersectionality literature, continuing an erasure of Black feminist knowledge in the academy. For instance, one paper defined intersectionality and provided Gender Shades as a citation, a paper that studies intersecting subgroups without ever mentioning intersectionality. But even among papers that use appropriate citations, many then dilute their definitions of intersectionality, neutralizing their (and readers') engagement with power structures and inequality.

Re-imagining the future of intersectionality in AI research

Our main hope is for more precision in how AI fairness researchers talk about intersectionality, through intellectual and citational vigilance when translating scholarly work across domains. This means that we expect AI fairness researchers using intersectionality to centre people at the margins, to build relationally (in community with users), to name their power, and to cite the people these ideas came from. And conversely, when researchers do work that is not about intersectionality but about intersectional subgroup fairness, they should be precise in calling it intersectional subgroup fairness, not intersectionality. Precision and rigour in how we treat intersectionality should be expected at every level - from our colleagues, reviewers, in industry and academia.

When it comes to system-building, smaller, scoped and iteratively built solutions in community with users is better. Computer scientists hate when I say this because our discipline encourages us to build universally, neutrally and quantifiably, but social contexts vary widely, all knowledge is situated, and quantitative and legalistic definitions of fairness are limited in their power (and sometimes even harmful). Combinatorial explosion with intersectional subgroups would not be an issue if we replaced solely quantitative measures of fairness with more expansive, people-centred ones - definitions that might look more like gathering people together for designing, iteratively developing and evaluating if, what, where, why and how any tech solution should be used and built.

Further reading

Our paper is now available (open access!) on the ACM digital library:

Factoring the Matrix of Domination: A Critical Review and Reimagination of Intersectionality in AI Fairness

Anaelia Ovalle, Arjun Subramonian, Vagrant Gautam, Gilbert Gee, and Kai-Wei Chang.

AIES, 2023.

If you're interested in reading more about intersectionality, I recommend looking up Kimberlé Crenshaw, Patricia Hill Collins, Nira Yuval-Davis, Sirma Bilge, Lisa Bowleg, Nikol G. Alexander-Floyd. I've particularly enjoyed:

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.

- Guidroz, K., & Berger, M. T. (2009). A Conversation with Founding Scholars of Intersectionality.

- Alexander-Floyd, N. G. (2012). Disappearing Acts: Reclaiming Intersectionality in the Social Sciences in a Post-Black Feminist Era.

- Bilge, S. (2013). Intersectionality Undone: Saving Intersectionality from Feminist Intersectionality Studies.

- May, V. M. (2014). "Speaking into the Void"? Intersectionality Critiques and Epistemic Backlash.

- Next post: In Memory of Jon: Reflections on Crip Linguistics

- Previous post: Skull-spotting in Saarland

- Back to the archive